4th Industrial Revolution as a workforce planning issue

The ‘new world of work’ of the ‘4th Industrial Revolution’ is one of the major topics of our time, being the central topic of the 2019 World Economic Forum in Switzerland in February this year; one of President Cyril Ramaphosa’s main themes in recent speeches; the focus point of SABPP’s 2020 to 2030 Strategy, unveiled at the June AGM; and the theme of the 2019 SABPP Summit to be held in August.

To many people, the developments in technology which epitomise the ‘4th Industrial Revolution’ are far removed from the current reality of our workplaces. It is hard to see Artificial Intelligence on a construction site, in an explosives’ factory, in a clothing boutique. It is hard to see ‘The Internet of Things’ as we do our weekly shopping.

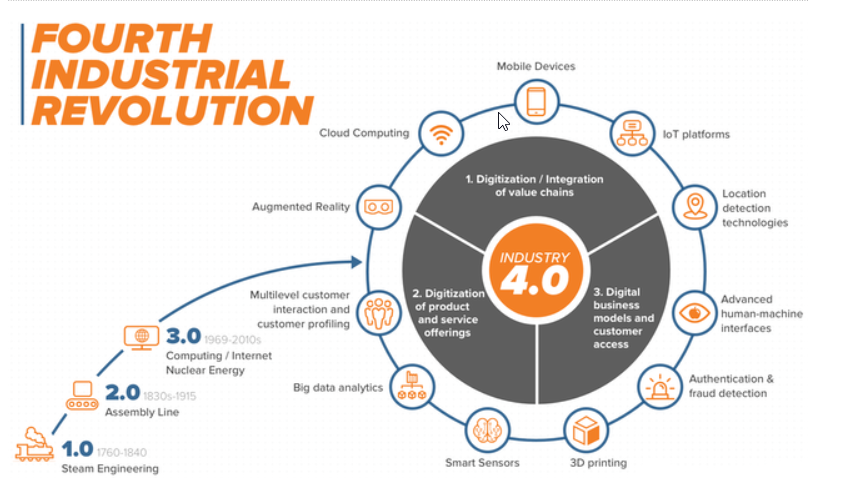

But if we look at the diagram below, we can identify some of the components as impacting on our work and personal lives already. For example, mobile devices are becoming more and more indispensable at work, at school, at play and at home. Location detection technologies are used to find our stolen cars and to help us find our way around (but don’t forget that constant use of our GPS’s is likely to shrink that part of our brains which create our internal maps – “A new study finds that when drivers rely on GPS to navigate around cities, areas of the brain used for navigation and planning “switch off.”[1]). Cloud computing saves us from losing data when our hard drives crash.

The advent and future trajectory of the ‘4th Industrial Revolution’ is going to be a journey, not an event and, as Rob Bothma said at the SABPP AGM, “it’s not disruption if you are ready for it!”, so a careful analysis of what technology developments in your industry are likely to take place over the next few years is essential. The journey must also be managed to achieve what policy makers are terming a “just transition”. This means re-skilling rather than retrenching workers.

An interesting example was in the media during July when MTN described how it is positioning itself to compensate for declining voice calls. “That same agent who is receiving cash and dispensing airtime in future can also dispense e-money, can sell insurance products and provision you for digital services” (MTN Group CEO, Business Day, July 15th 2019). Large banks in South Africa are introducing Robotic Process Automation in their call centres and re-skilling staff to perform more value-adding activities. Another example was also in the media in July when Ford announced a third shift at their Pretoria plant to meet the surging demand for the Ford Ranger. “Job losses as a result of technology innovations such as robotics have been balanced out [in the vehicle manufacturing industry in South Africa] by new investments and production increases” (Business Day, July 18th 2019). This illustrates that where technology development helps to expand markets and therefore turnover, this has wider benefits for people.

This point is elaborated on in an article on 5 Problems with the 4th Industrial Revolution by Tim Unwin, Chairholder, UNESCO Chair in ICT4D (source as above Footnote 1). His argument is that investments in the new technologies are largely driven by entrepreneurs and ‘big business’ to support wealth creation, and therefore potentially cause greater levels of inequality in the world. Even more care is necessary therefore to harness new technologies for social good and to manage the transition to reduce rather than increase poverty and inequality. Professor Alison Gillwald highlighted the work of the Fairwork Foundation (Business Day, 11th April 2019) which has set standards for practices in the ‘platform economy’ (businesses such as Uber): fair work; conditions; contracts; management and representation. The Foundation will measure all major platforms in SA (and internationally) annually and publish a league table.

Part of managing the journey is to make sure that the right conditions are in place to enable the use of the new technologies. Commentators have pointed out that, until the ‘3rd Industrial Revolution’ is fully in place, with high speed data, universal coverage and access and even ‘1st or 2nd Industrial Revolution’ infrastructure such as road and rail networks, the full benefits of new technologies will not be realised. In South Africa, one element of older infrastructure that needs to be brought up to date is the education system, and affording educational opportunities to the large part of the population that was forced to drop out of the system. Work is increasingly being done to bridge some of these infrastructural deficiencies. Allon Raiz, a long-time developer and supporter of entrepreneurs, described in January 2019 how dairy farmers in Somalia overcame barriers by developing small-scale solar-powered milk pasteurisation units which enabled them to transport longer-life milk to urban markets (Business Day, January 17th 2019).

We also need to develop a realistic idea of how long that journey might take. Ryan Crawford, IT Manager at tyre manufacturer Bridgestone SA, said in 2018:

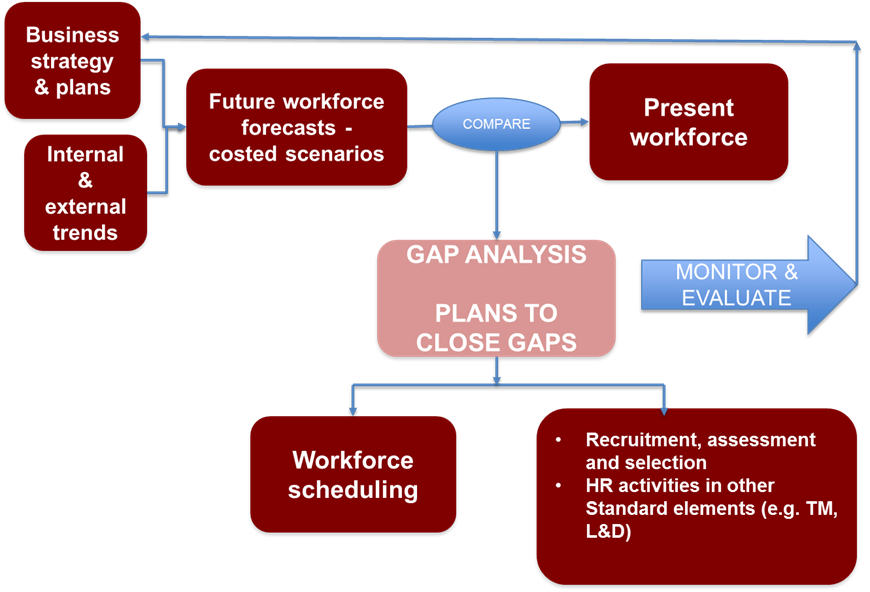

The definition of Workforce Planning in the SABPP’s National HR Management Standard is:

Workforce planning is the systematic identification and analysis of organisational workforce needs culminating in a workforce plan to ensure sustainable organisational capability in pursuit of the achievement of its strategic and operational objectives. The workforce plan will set out the actions necessary to have the right people in the right place at the right time.

This well describes how HR should be contributing to planning the journey into the ‘4th Industrial Revolution’. The fourth objective of this Standard is: “To ensure an adequate supply and pipeline of appropriately qualified staff through sourcing staff and building the future supply of the right skills to meet the needs of the organisation”. The process for workforce planning is set out in the Standard as:

The Application Standard explains further how to construct the likely future workforce. In addition, the risks identified with choosing various different future scenarios should be identified and analysed.

In conclusion therefore, HR practitioners must become expert at analyzing and predicting future changes affecting the workforce, must develop a realistic view of when and where those changes will impact, must influence the Board and executives to approach the transition from a values-driven point in order to ensure a just transition for the organisation’s workforce and, by extension, society as a whole. To quote Rob Bothma from the SABPP AGM again: “HR is currently under the table in the boardroom. Get off the floor, be the referee, set the rules!”. The workforce planning approach gives us the tools to do so.

DR PENNY ABBOTT: MHRP

SABPP RESEARCH AND POLICY ADVISER