As we settle into the realities of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the lockdown to arrest and address it, we are confronted with many different feelings, emotions and thoughts. We try to make sense of our own jumble of feelings, emotions and thoughts and that of others, and how our lives have been disrupted. These leave us at a loss for how to respond and what is it that we can do. This is especially the case with the news from across the world of the devastating effects and tragic deaths caused by the pandemic. We may feel even more isolated and emotionally charged during the lockdown because of these continuously streaming images and stories, especially from Italy and now the US where their healthcare is stretched, and the local count of those diagnosed with COVID-19 and those that we sadly lost. We may experience the necessity of social distancing as social isolation; and may sit with waves of emotional energy that we do not know what to do with.

It is important then to recognise, differentiate and acknowledge our different feelings, emotions and thoughts. It is normal to have these in reaction to the pandemic and lockdown. Only when we acknowledge these feelings, emotions and thoughts then can we express and understand them and their importance. This can be hard because we may find it difficult to consciously accept and deal with the mixed feelings and emotions; we may not be able to describe and make sense of our mixed feelings, emotions and thoughts; and we may experience racing and fragmented thoughts. Certainly, sitting with mixed feelings, emotions and thoughts can feel as if you on a rollercoaster ride.

We need to take the time to pause, reflect and work through these different feelings, emotions and thoughts. This means taking a break from the constant, streaming news and messages and setting a time and place to sit and reflect or have a focused conversation with someone you trust. Experiment with what you find comfortable and facilitates your reflection – whether it be writing down and mapping out your different feelings, emotions and thoughts; visualising these with images; visualising with others with different mediums; talking these through with yourself or with the help of others; ‘taking stock’ in a structured or unstructured manner; or making a list and setting up time slots to check, add and edit it.

If you are struggling to reflect then think about what helps you to relax, and what spaces you find helpful to think in. Try these activities and spaces to put yourself in a more relaxed and reflective mode. If you are struggling then try relaxation exercises such as breathing exercises, meditation, yoga, or classical or other relaxing music. If you are struggling to find the words to name your feelings, emotions and thoughts then explore feeling and emotion vocabularies or lists. There are many that can be found with an internet search. An illustrative example is provided below. In the section that follows there are descriptions of some emotions and associated feelings that people can experience.

Source: https://www.vocabulary.com/articles/wl/get-into-the-mood-with-100-feeling-words/

Many respond to tragic, life-threatening and disruptive events with anxiety, hopelessness, helplessness, sadness or depressed mood, angst, grief and guilt. They may find it hard to acknowledge these emotions and feelings at times; or may be in denial. This can result in the acting out of these emotions in ways that they are not aware of and are not constructive. For example, becoming short and curt with others, arguing unnecessarily, being aggressive towards other, being hyper-critical of others, and throwing temper tantrums. This could come through in how you communicate on emails, your demeanour and interactions during video conferencing, how you address and relate to others, and your lack of consideration for others. Becoming aware of, acknowledging and understanding that we are acting out does not condone it. It does provide us an opportunity to reflect and change.

We need to recognise that we may act out more during the lockdown, that is, act out emotions we experience with being confined in a closed space for a prolonged period (although it is our home), with feeling restricted in our movements, and from a sense of loss of control. Again, understanding why may act out does not condone the behaviour. It is an important signal that we need to pay attention to what is happening internally (our feelings, emotions and thoughts) and how we are expressing this. To help with this the below section discusses some of the emotions we may be experiencing and struggling with.

Anxiety

It is important to remember that anxiety is one of our human emotional responses. We all experience anxiety in our day-to-day lives at different times for different reasons. It is an adaptive capability that has evolved over time for navigating and surviving the world so we can respond appropriately when in danger. Firstly, anxiety acts as a signal to us of an impending threat or harm, for example, a potential external threat to our physical wellbeing and integrity or harm to our psychological wellbeing and integrity from internal psychological dynamics and conflicts. It differs from fear in that it is not caused by a specific, known object, person or event that is present and will cause harm. Anxiety, secondly, primes us and mobilises our body to respond to this potential threat or harm. This signaling, priming and prompting capabilities form part of our neural basis (brain) and behavioral repertoire for surviving (and responding to danger), and thriving.

This means feeling anxious at these challenging times of the pandemic and lockdown is not abnormal. It is part of our survival and adaptation mechanism. We should not disown it or try to avoid or deny it. For example, initially during the lockdown we may feel discomfort from disruption to our routine and being confined in a closed space with others for long periods (although we are in our own homes, we cannot escape others); feel unsettled by the restrictions on our movement and new ways of working such as remote working; and panic from feeling a loss of control. However, where these persist and intensify and we become completely paralysed by it, feel continuously stuck in cycles of negative thoughts and reactive responses, or continually responding inappropriately to others, then we need to address it.

Where it becomes debilitating, disabling and causes dysfunction for prolonged periods then we may need to seek additional support and where necessary help. This means that the anxiety may be maladaptive to the extent that it is clinically significant, where it is causing emotional, social and/or occupational dysfunction. For guidance seek professional wellness advice and help; and see, for example, this description of a generalised anxiety disorder and the resources of the South African Depression and Anxiety Group (SADAG). It is important to note that we can experience anxiety and depression together.

Grief

We respond to loss, particularly the loss of a loved one, with grief. As with anxiety, it is one of our human emotional responses. During the pandemic and lockdown, we could experience losses of different kinds – physical, symbolic and abstract. For example, the death of loved ones, colleagues, fellow compatriots and global citizens; the loss of our taken for granted ways of living, working and playing; loss of our comfort zones; and the possible loss of income and/or employment. For many disadvantaged communities the loss is stark and physical, with the real possibility of not having any food and shelter.

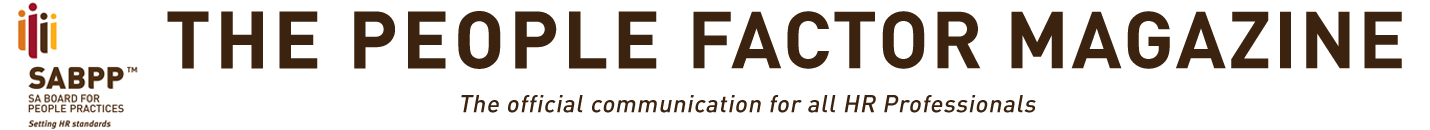

Generally, our response to loss evolves over time as we work through our mixed emotions and feelings. There are no clear phases or linear process to working through loss. However, many are familiar with the popular interpretations of the Kubler-Ross model. In this interpretation grief is described as comprising five stages, as depicted in the figure below. This can be helpful guide, but we need to consider that how we experience and work through grief is shaped by our different cultural and religious norms and our different familial experiences.

Source: Wikipedia/U3173699/ https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=81674970

Kubler-Ross developed the above model for how we each face our own mortality. We may find it hard to acknowledge and reconcile our own mortality. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, is forcing us to do that. So, we may experience existential angst and may not be aware of it.

Hopelessness and helplessness

We may respond to the pandemic, especially now with the lockdown, with the sense of helplessness and hopelessness. The Centre for Disease Control (CDC) provides these helpful definitions:

“Hopelessness is the feeling that nothing can be done by anyone to make the situation better. People may accept that a threat is real, but that threat may loom so large that they feel the situation is hopeless. Helplessness is the feeling that they themselves have no power to improve their situation. If people feel helpless to protect themselves, they may withdraw mentally or physically and fail to take actions to protect themselves and their families from the emergency” (CDC, 2017)

It is important to recognise when we are caught in a reinforcing cycle of hopelessness and helplessness. We may make the error in thinking that no preventative measures will help, lose perspective, and put ourselves and others at risk. If you unsure of the recommended preventive measures and ways to manage through the pandemic see the SABPP factsheet on the coronavirus and COVID-19. Staying at home keeps yourself and others safe.

What is the role of the HR practitioner?

As HR practitioners, we are not immune or devoid of the above emotions, feelings and thoughts. We need to first recognise, acknowledge and understand our own emotional reactions, and identify where we may need support and help. In our professional role where we focus on others’ wellbeing and that of the organisation, we can help others recognise, acknowledge and reconcile their mixed feelings, emotions and thoughts. In this way we normalise and help them take ownership of their different feelings, emotions and thoughts. It is only when they take ownership of these, then they will be open to the wellness strategy, support and resources you put in place. They can partner in reducing the risk from health and wellness issues. For guidance see the SABPP Employee Wellness Standard.

2 comments

Thank you for this most insightful and appropriate article.

Thank you, Sean, for your valuable feedback. It is appreciated and it gives us guidance on whether we are connecting and speaking to our fellow professionals and SABPP members, or not. There is a follow-up article that will be published on the SABPP blog on managing our emotional reactions.

We are also planning a series of focus groups to create a (virtual) space to explore further how our fellow peers are experiencing the pandemic, lockdown and its after effects, and how they trying to manage through it. The first will be on the 7th of April. Details will be provided soon. I will email you the details as soon as it is finalised.

Take care and be safe.

Kind regards,

Ajay