(This article was first published on 15 September 2019 by Tim Cohen – Business Maverick)

The requirement to have a secret ballot prior to establishing a legally protected strike is now law in South Africa, generating some speculation about whether it will help temper strike intensity and quantity. But it has also, inevitably, become an issue in itself, with Cosatu breakaway unions now threatening to take the issue to the Constitutional Court, in order to get it overturned. How does this all play out?

Nedlac’s great achievements in the recent past was the agreement on a new and higher minimum wage. But the agreement came with a caveat insisted on by business: that to have a legally protected strike, workers would have to first have a secret ballot. That has not been put into practice and it’s causing some growling and grumbling. Reconstructing motivations and history a little freely, it seems the logic behind the move worked something like this: for business, it was clear that they were going to lose the issue of a higher minimum wage in Nedlac. The government was strongly supportive, as were of course trade unions and the community groups, over-riding business’ argument that a higher minimum wage would reduce overall employment – an argument which, as it happens, has now been corroborated by history, at least in the short term.

In any event, business proposed a concession from the other groups as a condition for supporting the higher minimum wage; and that concession was secret ballots prior to strikes. Their argument was that SA is a massively strike-prone country – something the unions and some academics deny – and that strike ballots could reduce gratuitous strike action informed by things like a competition between union organisations. They also could reduce strike violence because a huge number of strikes in SA are associated with violent intimidation.

Just to take one recent example of how a failed strike can hurt, the recent Amcu strike at Sibanye Gold lasted five months, left nine people dead, reduced Sibanye gold output by about 110,000 ounces of gold worth about R1.6-billion, it will take the Sibanye strikers about 15 years to earn what they lost in wages during the strike, and they gained nothing more out of the strike than NUM workers gained. The sheer all-round destructiveness that strikes involve is now getting some belated recognition from the government, which acceded to business’ demand.

From the unions’ perspective, the toss-up between getting a higher minimum wage and simultaneously conceding the strike-ballot issue was a tricky choice, but on balance, worth it. Ballots are already often taken before strikes, albeit not secret ballots, so it didn’t seem like much of a concession in the real world.

But there is a complication here – a big one. Because of the traumatic split in Cosatu in 2014 and subsequent departure of the National Union of Metal Workers of SA (Numsa), a big chunk of the union movement was not represented in Nedlac at the time the agreement was struck. That wasn’t for lack of trying; they applied but were refused notionally on the basis that the South African Federation of Trade Unions (Saftu) had not provided audited financial statements and audited membership figures and other documents.

Arguably, because Cosatu is now predominantly a state-sector union, it was less motivated to reject the idea of secret balloting because it is anyway protected by its ally, the ANC, being in control of the state. Cosatu’s strength now lies primarily in its link to the ANC rather than on the shop floor, cynics would say, making it more difficult for the union to differ with government on key policy issues.

The way the new legislation has unfolded has however given Saftu and Numsa an opening because they were not part of the grand compromise, and it’s inevitable that they are going to make hay over the issue.

Earlier in September, Saftu said in a statement that the “secret strike ballot is a Stalingrad tactic meant to fatigue workers and unions from exercising their constitutionally guaranteed right to strike meant to diminish the already shrinking power of the working class.

“The decision emanates from a class collaboration that took place behind closed doors at Nedlac between government and sweetheart unions who signed on to this sellout deal with no mandate from their members,” the statement says. Numsa is in strong support.

Saftu general secretary Zwelinzima Vavi told Business Maverick that the legislation had already caused two strikes in the country to be declared unprotected, which was evidence of the union’s claim that the legislation is going to be used to suppress strike action.

Furthermore, the legislation has been poorly drafted, he said, because although it requires a plurality of votes to approve a strike, it does not specify what proportion of the workforce needs to vote.

Saftu, with support of other unions, has resolved to take the legislation to the Constitutional Court to have it struck down. Cosatu, clearly trying as hard as possible to stay under the parapets over the issue, hasn’t responded to the issue and didn’t respond to Business Maverick’s questions.

These developments initiate two new questions in SA labour relations: first, will the secret ballot requirement, in fact, reduce strikes? And second, what chance do the challenging unions have in the Constitutional Court?

Like almost everything in SA’s labour relations, the likely effect of secret ballots is disputed. The acting head of Business Unity, Cas Coovadia, said SA is a strike-prone country, but at this difficult economic moment, the really crucial thing is for everyone in SA to focus on working together to improve economic growth. Secret ballots could help in that process, so BUSA supports them.

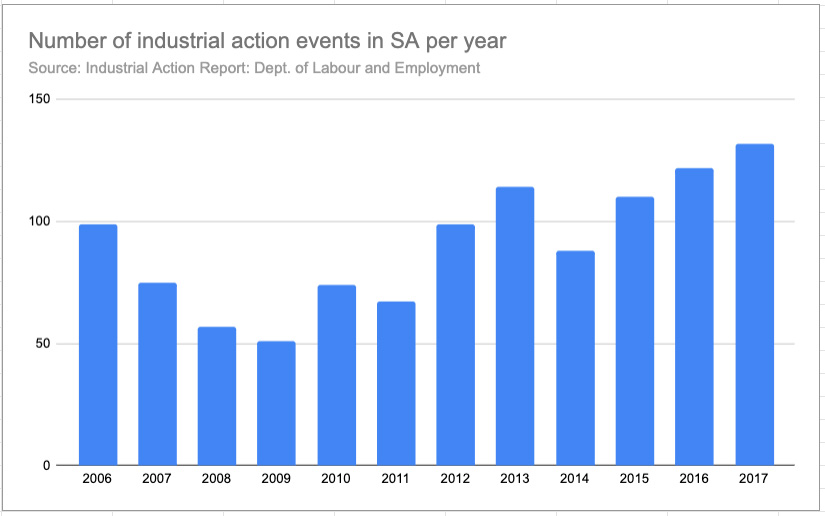

There is some academic disagreement about whether SA is actually a strike-prone country, but it’s probably fair to say it is. The easy calculation just counts the number of strikes, and those have been increasing every year, so that 2017 – the latest date official data has been released – had 121 strikes, the largest number for a decade.

The more complicated calculation is to measure the number of workdays lost per 1,000 workers per year. In 2017 in SA that number was 59.2 according to the Department of Labour and Employment’s Industrial Action Report. The global average is around 30.6 days. But the numbers are very variable, and it depends a lot on how you categorise informal-sector workers. Still, the overall gist is that SA is very strike-prone, and it’s undeniable that strikes are very violent.

Another reason business probably supports strike ballots is that it reduces the power of aggressive union activists to bully workers into having a strike, so would reduce the power, for example, of non-government supporting unions such as Amcu and strengthen unions in the government sphere such as the National Union of Mineworkers. Nobody in business or government, for that matter, thinks that’s a bad idea.

The second question is equally perplexing: what are the chances the Constitutional Court will support Saftu’s challenge? Section 23 of the Constitution says, “everyone has the right to fair labour practices” and protects the right to strike. But it also says, “national legislation may be enacted to regulate collective bargaining”. That is, however, itself governed by the so-called “limitations clause” which requires government legislation to be “reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom”. You remember? That idealistic stuff.

Are these clauses sufficient to bar the secret ballot measure, which is, after all, a common part of labour legislation around the world and not generally opposed by the International Labour Organisation?

(We will see. DM)